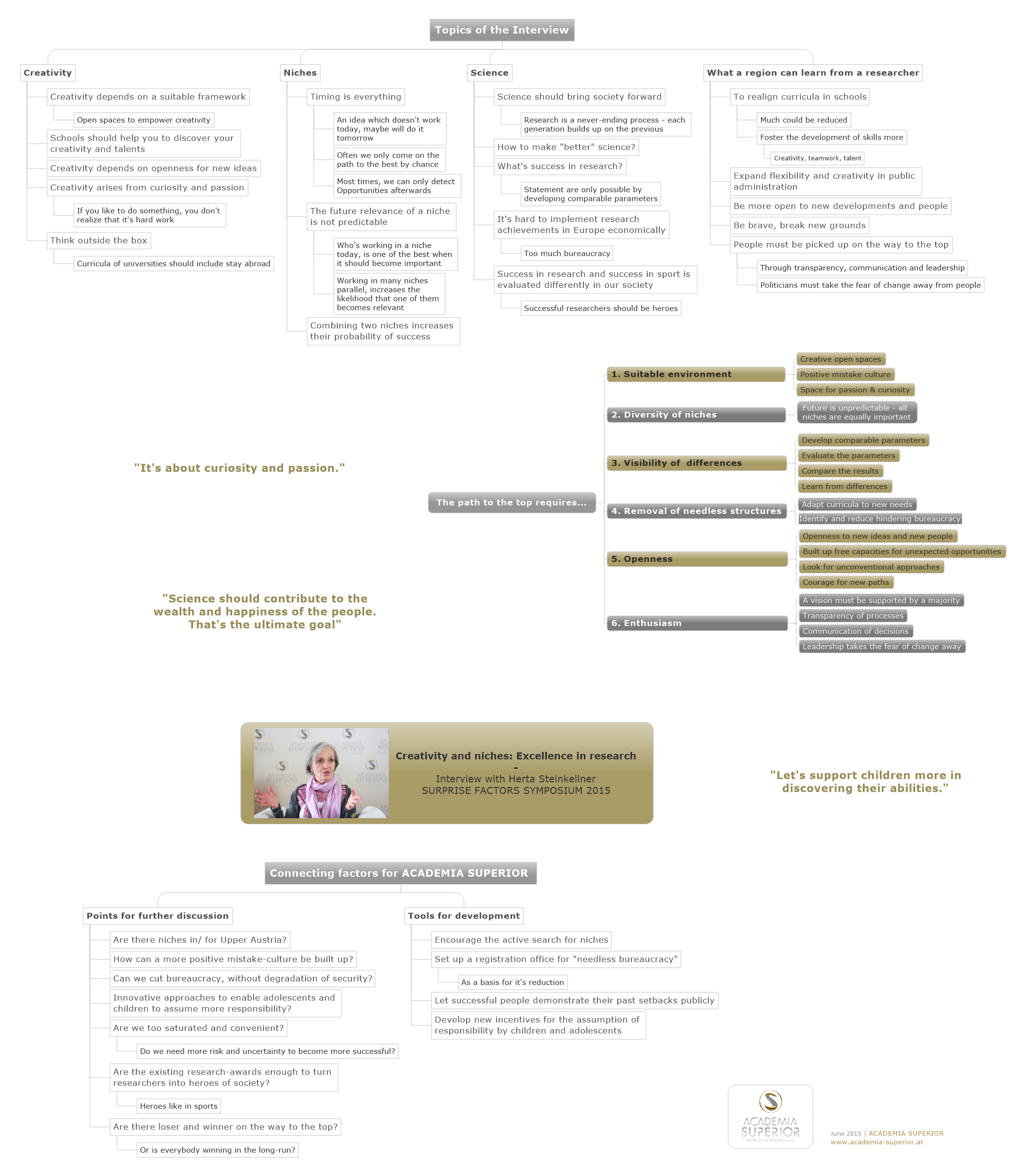

Molecular biologist Herta Steinkellner describes the path to the best from her own experience as a path of courageous decision, passion and the search for niches. She was one of the experts at the SURPRISE FACTORS SYMPOSIUM “From Good to Great” in Gmunden 2015.

Herta Steinkellner in the interview:

If you think of my life, my career, as a journey, I would have to say there was no master plan behind it. My family background has nothing to do with science. In the village where I grew up there were three high-education professions: become a teacher, become a lawyer or become a medical doctor. From those three options I chose to become a teacher. I went to Vienna and since I had to decide what to study, I chose biology. It could have been anything, but why not biology?

I realized as I was studying that I had extra time. So why not get a job, earn some money? I joined a human genetics lab to do basic work and it was love at first sight. I looked into the microscope and I started to realize a new sense of what I was studying and why I was studying it.

Niches in science

Just by chance there was a person at this lab who was starting a new technique in Austria, making cells from a human body grow in a Petrie dish. You put solutions into the Petrie dish and you can grow human cells without a body. This work needs regular “feeding” cells to keep them alive. I was so fascinated that I volunteered to come in at evenings and weekends for feeding these little things. Suddenly I was a person in Austria who could do an emerging technique that nearly no one else could do. I didn’t even think it was hard work, because I liked what I did. Actually, I felt privileged that someone would pay me for something that I loved to do.

When the Ebola virus work started, it was at a time when nobody was interested in it. Most of the large companies were going into cancer research, and there was no sense in competing with them. So I was looking for niches, and choosing that niche was a decision that I did make on purpose.

I found I was in a unique position. There was already a general technology that allowed the transfer of a human gene into a plant and then the plant would produce the human product. At the time I started working, there were two groups: you either worked on molecular medicine or on plants. The two groups were more or less separate. I was able to combine the two topics, to form something new. It was a result of bridging the two separate groups.

„It’s not about the plan. It’s about having curiosity and passion.”

But in the application of that science, the European culture didn’t work. A lot of basic science is done in Europe. But to transfer the scientific data into a commercial product, Europe was totally out. Even though I was member of a large consortium with 30 labs and companies in one of the largest European-funded projects, we still had the nightmare of working with the European regulatory agencies. We had a new technology and we wanted to go further but it was simply not possible. Regulatory authorities put conditions on what we had to do, what we had to show – it was simply too complicate.

At the same time I was attending scientific congresses all over the world. In 2008, when I introduced my plant based production system, two US-American companies asked for cooperations. I asked them, “You really want to work together? It’s so complicated.” It wasn’t complicated to them. Now the large scale production of a promising Ebola drug is underway.

One of the reasons I love this work is that it’s not just a two-year or five-year goal. It’s something that goes beyond just one life span. Knowledge and science accumulates from one generation after another. It’s a long-term issue and the success does not rely in a single person. It’s actually up to everybody.

Creativity and responsibility

Part of thinking about going from good to great is recognizing roadblocks that prevent people from making that journey. In Austria, to me, school-education has a strong tendency to be one of those roadblocks. I would radically change the educational system. I would cut the learning duties in half. With the gained time I’d encourage children to solve problems, to work out solutions, to develop their own creativity and to find their own talent.

I don’t think we have enough of a chance to show or to express our individual talents. If we support our children to find their abilities, to do creative work and to develop their own sense of responsibility, then I think everything else will take care of itself. That’s my own story. I followed my curiosity and took advantage of opportunities that were put before me. There was certainly no top-down plan from someone else of what was best for me. I think everyone has that kind of talent. They just need the chance to find it.

If we give our children a chance to find their talent, to do creative work and to develop their own sense of responsibility, then I think everything else will take care of itself.

People also need to be allowed to fail. In Austria, if someone starts a company and it fails, there is a long lasting negative spirit on that person. In the United States, if you fail, there are more possibilities to start again. People are allowed to learn from failure.

Finally an important question of doing science is “What is the goal”? For me, science should contribute to human prosperity and happiness. That is the ultimate goal, whatever we do.

How can Austria go from good to great? One way is to emphasize scientific achievements. For example, scientists should be treated like skiing heroes if they get good results. And indeed some Austrian scientists are excellent! They should get a gold medal and should be rewarded, also financially, to do even better. This is how we go for skiing, and the results are convincing! I am deeply convinced that Austria has the potency to become world champions in science if we follow the strategy we apply for winter sports.

About

teinkellner studied biology and earth sciences at the University of Vienna before she joined the BOKU Vienna first as a PhD student and then as a lecturer. During her studies she worked at the human genetics laboratory of the Vienna General Hospital, which sparked her passion for her later work.

In cooperation with other researches, Steinkellner developed tabacco plants in 2008 that produce human proteins. They can develp highly effective antibodies and are considered a promising therapeutic approach in the fight against the Ebola virus.

Due to theses achievements, Steinkellner was nominated as “Austrian of the Year” in the field of research in 2014. Steinkellner has co-authored numerous publications in journals and anthologies and contributes to scientific conferences.