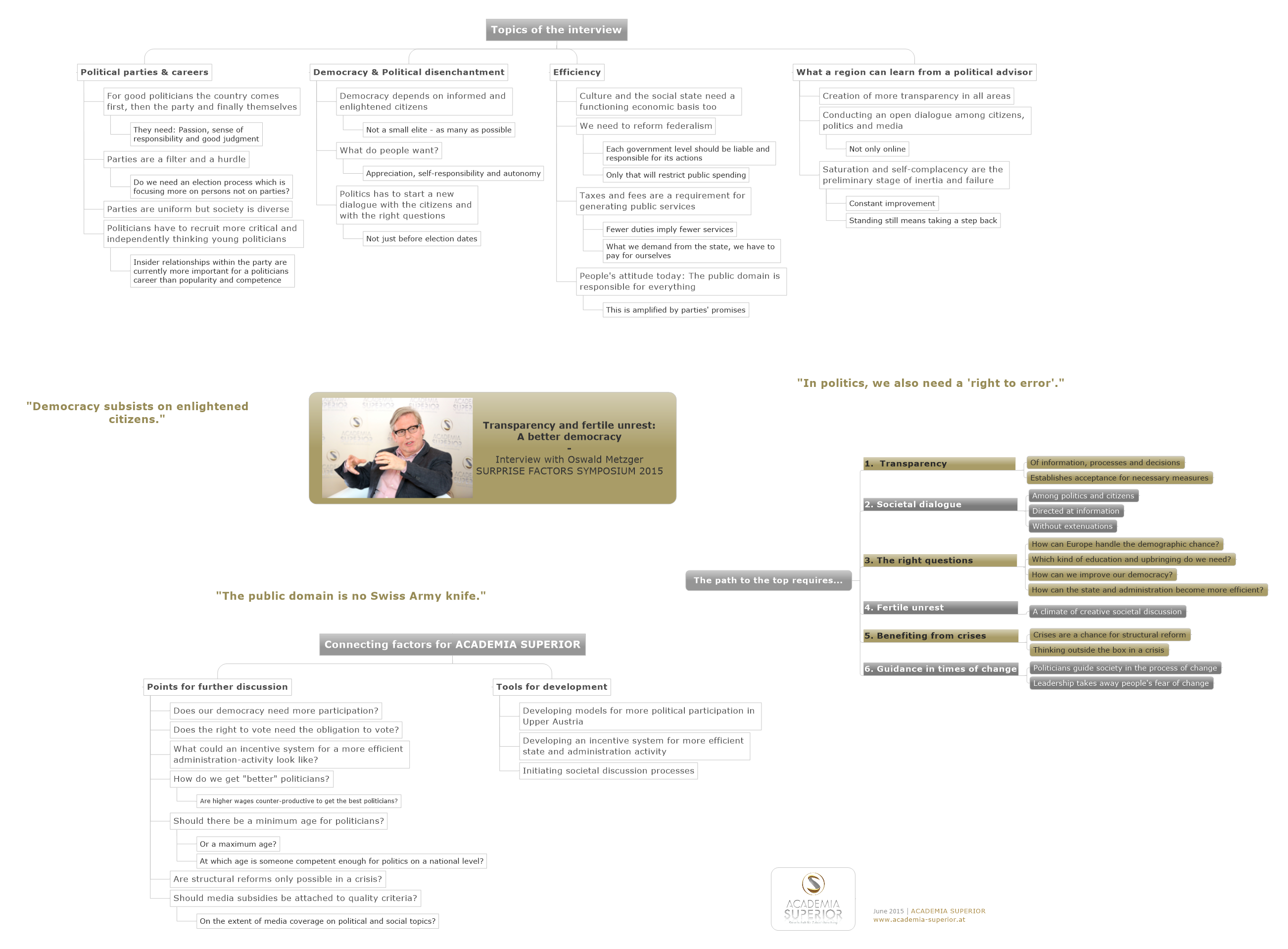

The political maverick from Germany and one of the experts at the SURPRISE FACTORS SYMPOSIUM “From Good to Great” 2015, Oswald Metzger, recommended an transparent and open dialogue between politicians and citizens in order to achieve acceptance for necessary measures on the the way to the top.

Oswald Metzger in the interview:

My career as a politician – and my journey from the SPD to the Green Party and then finally to the CDU – began when I was 19 years old. Willy Brandt was Germany’s Chancellor at the time and I was fascinated by him. So I became a member of the SPD. I grew up with my grandparents who were rather conservative working-class people. When my grandfather learned that I had become a member of the SPD, he told me, “Who is not left-wing in his youth does not have a heart; who is still left-wing in his old age does not have a brain.”

I worked for the SPD for six years as a volunteer and also as a member of the county board, managing the election campaign in the electoral district. Then I realized that my own personal views were different from the party. So in 1979 I got out and I made up my mind never to become a member of another party because of the pettiness, the small-mindedness that parties require. Then in 1980 the Green Party was founded, and since it was new and I was politically active in my community, but not as a member of any party, many people thought I was part of this new club. I figured, since everyone thinks I’m a member of the Green Party, I might as well join them. That lasted for 21 years!

„More personal responsibility is the key to a successful future of a society.”

Now one of the things that I did during the time I was a member of the SPD was to study law and then, because I came from really modest circumstances, I registered a writing office. At that time I was self-employed and I learned to be entrepreneurial and much more market-oriented in my economics.

„We need a ‘fertile unrest’ – saturation is the precursor of failure.”

As a result, when I entered the Bundestag as a member of the Green Party, I was called “the first Green politician who knows anything about money and economics.” Over 2 election periods (1994 – 2002) I was a member of the Bundestag and ready for a third one. But in 2002 – before the nominations for the next election took part – I dared to criticize the German Chancellor on television over his economic policy toward European Union. That ended up in not being nominated for the election in 2002.

I went back to work with the local Green Party in Baden-Württemberg. I got a seat in the local parliament at the election in 2006, but over time the Greens made a major shift to the left. When they decided that every person should have an unconditional basic income paid through taxes, I resigned. I told them, “You’re crazy. If you want to give everyone 800 Euros per month, regardless of need, you’re creating the illusion that money falls from the sky.”

So I left the Green Party at the end of 2007 and declared in the press to resign as member of the local parliament. My colleagues at the CDU then thought I should join them in the local Parliament in Stuttgart. But I wanted a clear cut – left the party and resigned the seat in the parliament. About six months later, I did, thinking to myself, “I’m joining a people’s party with a Ludwig Erhard, the father of the German economic miracle.” So today, having been a member of the SPD and then the Green Party, I am active in the economic wing of the CDU on the national level and I run a small, unusual think tank called “Konvent für Deutschland” – which consists of former top politicians from all parties in Germany. We consult for the public welfare for constitutional reform.

Experience in life teaches us that things only change if there is a crisis. That’s true in companies, in politics, in society. Reforms in good times are virtually impossible.

In politics, when I think of the journey from good to great, at the moment I have to conclude that we have incredible inertia in Germany. Today, in politics we have too many people who don’t stand for anything. In the past, we had statesmen in the best sense of the word: The country comes first, then the party, and then I. That’s one of those sentences that distinguishes a foundation of values by a statesperson. Those people are becoming fewer and fewer.

I think we’re making a big mistake in all democracies today. Democracy depends on a well-informed, enlightened, responsible population. People need to know about connections and interrelationships – and that goes for all people and not only the elites.

But the way in which we built Europe was an elite project. Political elites said, “Let’s put it together. Somehow it will work and the population will see the advantages: We’ll have falling boundaries and an improved exchange of goods and merchandise. We’ll have one common currency and transaction costs will go down.” But now you recognize that areas that have been thrown together are actually very different.

Once again you hear voices in Europe that we thought we’d gotten rid of with the unification process.There have never been as many centrifugal forces as today, as much hatred and prejudice.Any lawyer would say that the Latin phrase, “Pacta sunt servanda” – agreements must be kept – no longer applies to Europe. You write a fiscal compact, then two years later you throw it away. That is troublesome and frightening. If you want to have a well-informed population in a democracy, then you have to tell people the basics of social order.

What do we want as people? We want to be appreciated. We want to be taken seriously. We want to discover our talents, our skills, in our homes, in the education systems that we attend, in our jobs, and as customers. We want to be able to stand on our own feet, to make something of ourselves. If I stand on my own feet, then I make something of myself and I contribute to my community. But these basics are being lost.

Today we have re-educated our people to the mindset that the state will make everything all right. As an individual, I am entitled to steadily increasing benefits. But those benefits cost money. You have to generate that through fees and taxes before you can distribute checks to the public.

The state is not a Swiss Army knife. It cannot function as a jack-of-all-trades.

How do you create change? Experience in life teaches us that things only change if there is a crisis. That’s true in companies, in politics, in society. Reforms in good times are virtually impossible.

If you want to go from good to great in Upper Austria, you have to initiate a discussion about the future. You have to take along the mainstream media and address the different socio-political organizations. You need to infect the zeitgeist so the right questions are posed. Because if you don’t ask the right questions, you won’t get any answers from society. You need to trigger something like a “fertile unrest” – because being satiated, being complacent, being comfortable is a precursor of failure.

More about Oswald Metzger:

Metzger considered as a political maverick. His work and life as a politician are characterized primarily by one feature: sticking to his convictions.

Metzger started his political career in 1974 with the SPD, then he was a partisan and switched to the Green party in 1987 for nearly 21 years before he became a member of the CDU in 2008. Throughout his political career Metzger always represented his own opinion, even against established party lines.

In 2003, Oswald Metzger’s book “Einspruch. Wider den organisierten Staatsbankrott” (Objection. Against an organized state bankruptcy) was published, in which he publicly expresses criticism of the risky debt policy in Germany. In 2009 Metzger published “Die verlogene Gesellschaft” (The medacious society), in which he addresses and processes the socio-political dilemma of honesty in politics.

Since 2010 Oswald Metzger is deputy chairman of the small business association in Baden-Württemberg and executive secretary of the “Convent for Germany”.