By now it should be clear that the over-arching theme of the SURPRISE FACTORS SYMPOSIUM doesn’t deviate from year-to-year. The through-line that connects each year is change. How do we anticipate change? How do we make sense of change? How do we use change to make the lives of the people of Upper Austria – and people everywhere – better?

This year the familiar theme of change came to us with an unfamiliar twist: “Out of Control?” Simply to ask the question is to acknowledge that we are, in many ways, in unexplored territory. In the wake of Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, a rising tide of nationalism stoked by increasing incidents of terrorism, it’s not only fair to ask if things are out of control, it’s timely and essential.

It’s a question that invites other questions: Where are we when it comes to world affairs? How did we get here? Are we witnessing the unraveling of a series of understandings, formal and informal, that gave us 70 years of relative peace and prosperity? What happens next?

„What does democracy look like in a picture?”

To help explore these questions, ACADEMIA SUPERIOR invited three gifted individuals from different walks of life: Andrea Bruce, an award-winning photojournalist who has spent more than a decade covering the chaos of war in the Middle East; Lord Brian Griffiths, influential policy advisor to Margaret Thatcher, seasoned business leader and member of the British House of Lords; and Kai Diekmann, visionary journalist at the Bild Zeitung, close observer of Silicon Valley and advisor to media platforms all over the world. What did we hear?

Even in the most war-torn parts of the world, where bombings and acts of violence truly are out of control, humanity has a way of shining through. There are rituals and practices that cut across cultures to connect us all – perhaps most profoundly, death, funerals and mourning. Sometimes daily-ness is more compelling than the disruption of daily-ness: After a bomb went off, there is shattered glass, there is demolition – and then there is the need to sweep up, pick up and carry on. There is the recognition that images often carry emotional information that words can never convey.

And from Andrea Bruce there is a suggestion: Democracy is at risk if we don’t examine it, understand it, engage with it and participate in it. One way to embrace democracy is with a community-based photography project – a project Upper Austria could launch: What does democracy mean to you? What does it look like in a photograph?

„People who feel they aren’t being listened to suffer a profound sense of loss of control.”

We also heard that sometimes the feeling of a loss of control triggers a political event that others fear represents an even greater loss of control. Behind Brexit was the sense on the part of a majority of the British electorate that they had lost control of their own justice system and their own immigration policy. There was a feeling of anger, even resentment by the “somewhere people” – people who are rooted to a particular place and a particular way of life – that they were losing control in their lives, having it taken away by “anywhere people” – people who are citizens of the world, operating in the global economy. People who feel they aren’t being listened to suffer a profound sense of loss of control. Brexit in part reflected that feeling.

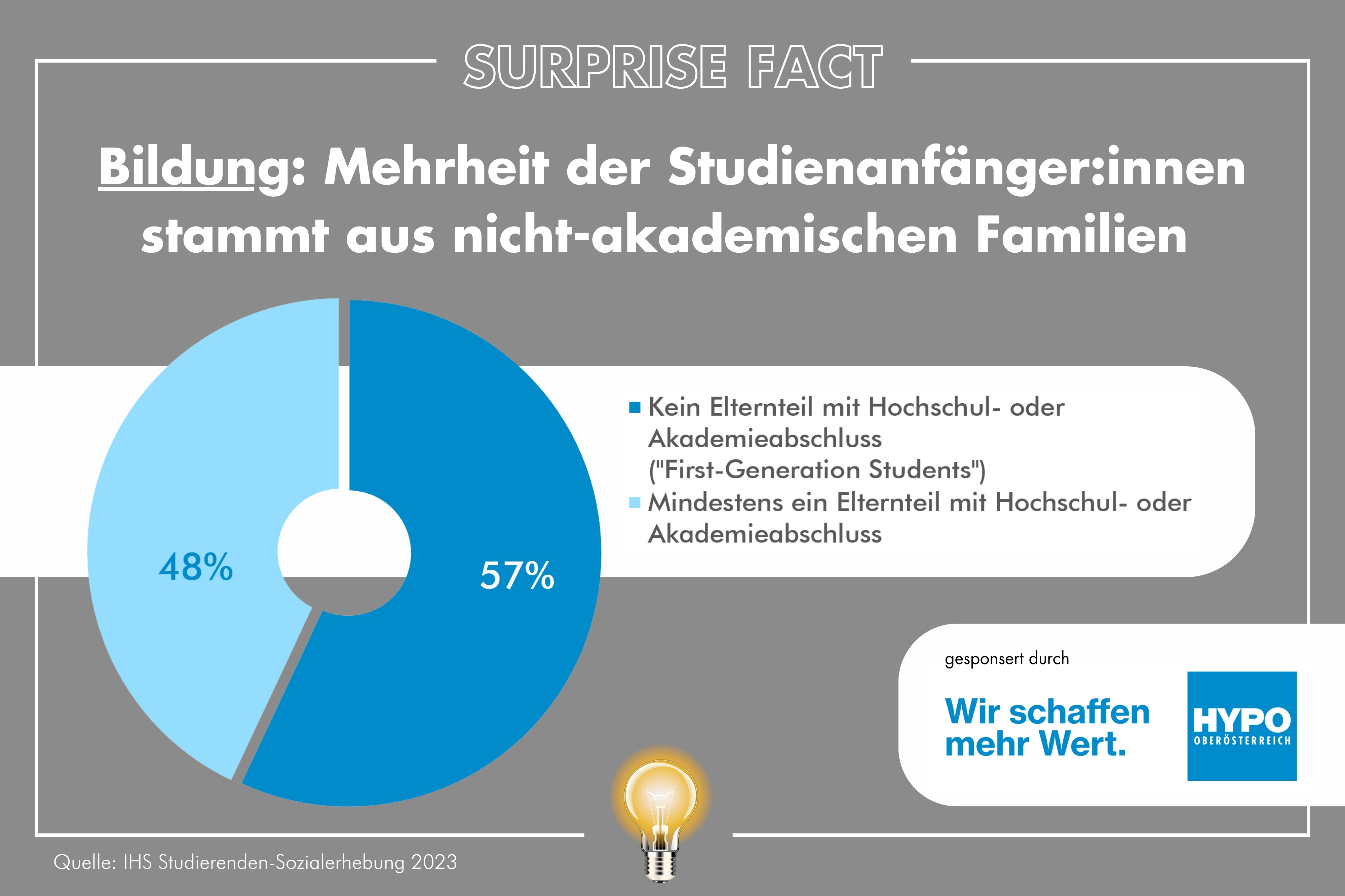

From Lord Brian Griffiths came another suggestion: Regions such as Upper Austria should find ways to stand out as their own place. Insist on authority that allows differentiation and the ability to showcase what makes them unique. And another: Don’t walk away from vocational and technical education in pursuit of higher education. To keep a healthy, thriving middle class means continuing to respect and honor the working men and women who make things, fix things, repair things and connect things.

„Journalists have failed to see the changes in their own line of work coming.”

Finally, we heard about the intersection of media and public affairs. Here we learned that the media and journalism are, themselves, out of control. The business model is broken. The traditional monopoly on news gathering and news distribution has been disrupted. An industry that supposedly thrives on change has resisted change. Journalists who prize curiosity have retreated from curiosity as it concerns their own work and lives. Instead, media today are in the clutches of algorithms that feed us back more of what we’ve identified as the things we’re interested in. As a result, the public conversation suffers. Our ability to understand and adapt to change is diminished. We become more and more isolated in information bubbles of our own making.

„Maybe, in times like these, pessimism is our friend.”

From Kai Diekmann we heard a few suggestions of the way forward. We must remember that communication is first and foremost emotional, not rational. We need to embrace the reality of emotions, use emotions to get important messages out. Remember that people are visual creatures: Images are more accessible than words. And try to reinforce history: We can’t afford to lose track of where we’ve been, how we got to where we are, and what we would lose if we walked away from the hard-learned lessons of the past.

Finally, in an “out of control” time, we may need to use pessimism as a friend – a reminder that bad things can and will happen unless we work even harder to make better things happen instead.